Four Principles For Building Power in Media

2020-03-16

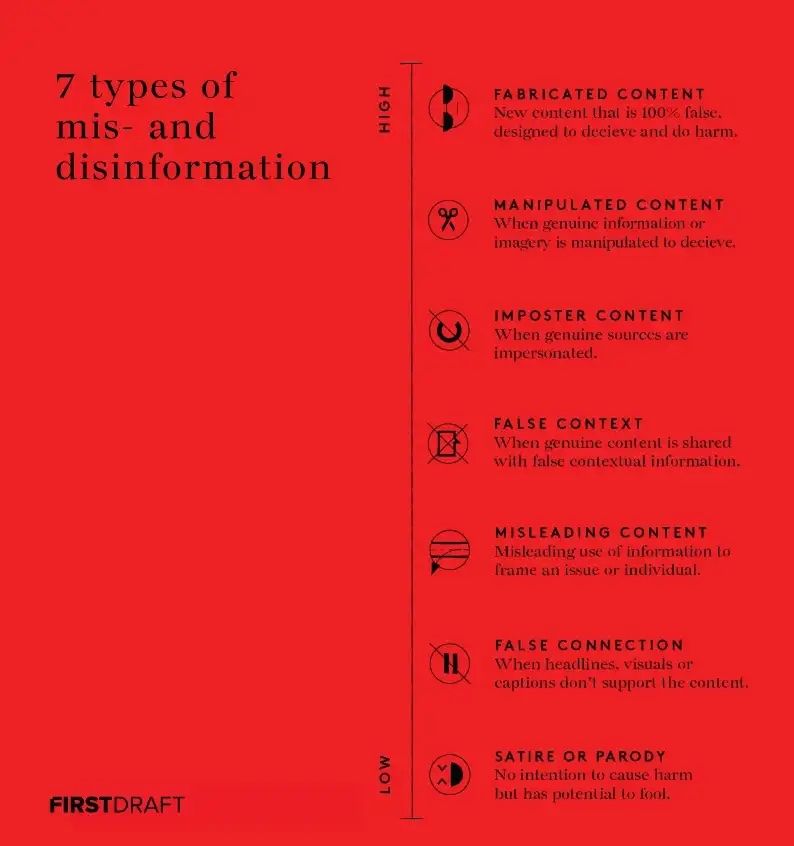

When we think about disinformation and the upcoming election, we should not think primarily about “fake news,” nor the hoaxes that routinely spring from the web’s dark loins. Rather, we should focus on the strategies intelligence agencies and autocrats have used for decades, if not centuries, to retain and project their power, to remove the conditions opposition needs to take root and flourish. Strategies like exacerbating existing social divisions by promoting particular types of media content within particular communities. Strategies into which our current media systems and personal digital dependencies have breathed new life. This is the message contained in the steady drip of disinformation stories the media has recently produced — like this one from USA Today or this one from The Atlantic — schooled by organizations like FirstDraft, which has been promoting a more inclusive, more accurate view of disinformation for years. This upgrade to mainstream understanding is good news.

Mis/Dis-information definitions from First Draft’s _Essential Guide to Understanding Information Disorder_

Mis/Dis-information definitions from First Draft’s _Essential Guide to Understanding Information Disorder_

There has not yet been a corresponding upgrade in our notion of what to do about disinformation, however. The same articles that observe this new reality — of persistent, global-local disinformation networks, of post-truth, of polarized echo chambers, or whatever — tend to dissolve in nostalgic paeans to “trust and truth,” to bygone days when a few experts or organizations established the “objective facts” that bound together we, the people. Alternately, these articles profile an ever-changing set of socio-technical initiatives to stem the supply of disinformation, to remove, fact-check, label, or otherwise disadvantage content deemed ill-intentioned, questionable, or low-quality. Supply-side interventions like these are bound to play a role in whatever coping mechanisms we, the people ultimately develop, especially given the responsibility that platforms and their opaque algorithms bear for our exposure to information generally. But both the supply-side response and “trust and truth” nostalgia seem born of the same ongoing infatuation with technology and technocrats that may have gotten us into this mess in the first place. So what else can be done?

There was a moment in 2017 when media literacy seemed to be an answer. At that time, Facebook, California lawmakers, the James L. Knight Foundation, the American Library Association, and others were announcing initiatives to educate us back to civic health. These are detailed in the Data & Society report, “The Promises, Challenges, and Futures of Media Literacy,” a clear-eyed contextualization of media literacy and a caution against viewing it as a panacea for disinformation. Report authors Monica Bulger and Patrick Davison observe that media literacy “suffers from all the issues plaguing education generally,” such as wide variations in goals and intended outcomes, politicization, outdated underlying mental models, and a lack of a national evidence base. Nevertheless, Bulger and Davison offer a few ideas to focus media literacy’s future, for instance, developing and testing curricula that go beyond individual critical thinking outcomes to seek changes in community norms and behaviors. Media literacy theorist, Renee Hobbs arrives at a similar recommendation in her 2010 white paper, “Digital and Media Literacy: A Plan of Action,” but goes a step further. Hobbs suggests we “engage the entertainment industry’s creative community in an entertainment-education initiative to raise visibility and create shared social norms” regarding pro-social media behaviors. These two ideas point the way to a possible response that draws on, but ultimately extends beyond media literacy’s traditional bounds. What if we enlisted the very media systems and content — Silicon Valley and Hollywood — that disinformation exploits to build the community norms required for resistance and resilience in a post-truth information environment?

The idea of using media systems and content to update or influence community norms at scale is not new. In fact, it has proven remarkably effective across many communities and national contexts over the last few decades. Think “Sesame Street” as a response to falling literacy rates among low-income urban youth in the 1960’s. Consider how the gay porn industry, under activist pressure in the 1990’s, made condom use the norm in a community beset by HIV-AIDS. There’s the radio drama “Musekeweya,” which Rwandans have credited with helping heal ethnic divides after the 1994 genocide. South Africa’s “Soul City” television series fostered a significant shift in popular opposition to domestic violence. Viewers of MTV Africa’s television show, Shuga, are twice as likely to get tested for HIV. And, more recently, Hulu’s “East Los High” led to measurable improvements in knowledge of reproductive health practices in its young LatinX audience.

What we haven’t seen are these types of content and norm-changing strategies employed at scale to address citizenship and political participation in a post-truth information environment. People are starting to call for it though, as in this recent report from the National Endowment for Democracy, which observes, “Norm building is a common feature of governmental and nongovernmental efforts to pursue the public good in democratic societies. . . . We need to apply such norm building to the information space.” We would like to add our voices to these calls. In fact, we’ve already started experimenting.

Recently, we produced a couple podcast pilots. Our means were minimal, and therefore the scale of our experiments was small. Our intention was to use these pilots to help people better imagine what might be possible, with more partners and resources. The first podcast pilot, “Anomaly,” is a narrative fiction set in a near dystopian future. It follows 17-year old Kory Hernandez, as she travels from her family home in Queens to rural Illinois to wait out the wars and environmental hazards of East Coast USA.

The world and the narrative that unfolds serve as scaffolds for characters and situations designed to draw young audiences in, then model — through positive and negative social responses and outcomes — the attitudes and behaviors conducive to resilience in a disinformation-rich environment. The pilot also seeks to model — in the contrasts between key rural and urban characters — the plausibility of balancing small-town community-oriented mindsets with more open, expansive definitions of what it means to be American. These strategies were developed by applying an audience-centered social change framework to common media literacy skills and other related habits of mind, in collaboration with researchers, producers, talent, and young people, in a process analogous to what was used for VR Action Lab.

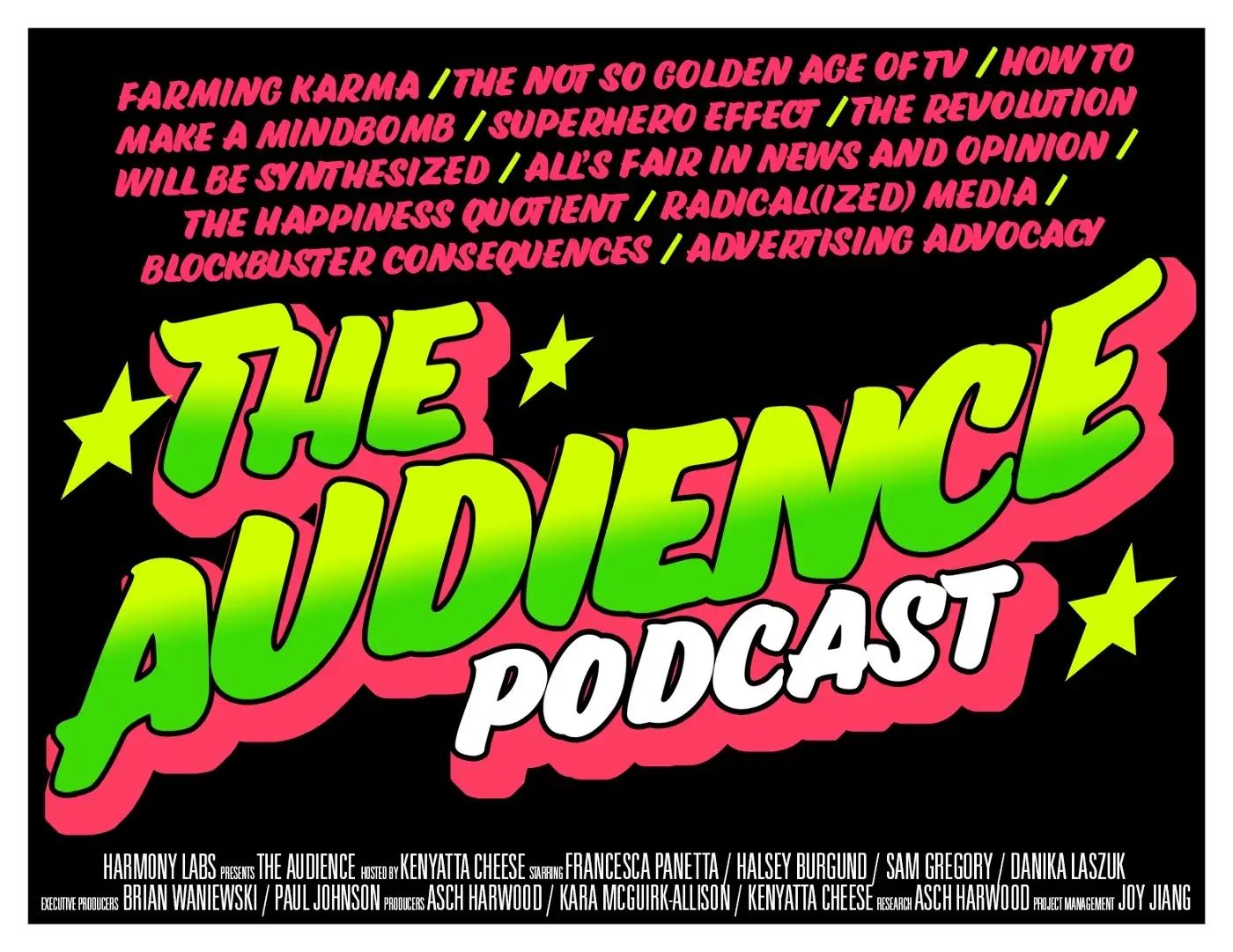

The second podcast pilot, “The Audience,” is a more traditional, journalistic look at what’s happening at the cutting edges of our media systems, and how these developments will affect mainstream culture. This podcast has a host, and each episode has a theme, starting with “The Revolution Will Be Synthesized,” around which we arrange a provocative collage of interviews, found and archival audio, and listener interactions.

We’re aiming for an unusual audience mix here: older folks (age 55+) and young people (ages 12–18). Our assumption is that each of these groups generally has something important to offer the other in terms of building media systems resilience: on the one side, greater fluency with emerging technologies and, on the other, a larger store of life experience from which to interpret new developments. The podcast will be supported by a few different curricula, designed specifically for informal learning institutions, like public libraries and community centers, as well as middle schools and high schools. These curricula will touch lightly on traditional media literacies, like critical thinking. Predominantly, however, they will focus on media making as a context for developing an embodied awareness of media’s effects on oneself, others, and communities, and then using this awareness to generate and reinforce the norms and behaviors likely to grow civic resilience.

The kind of content we envision and have already started experimenting with goes beyond “awareness-raising” or “tackling tough issues,” which is how entertainment-education has typically been used in the United States. And it is distinct from worthy projects like integrating scientifically accurate information into existing storylines, or increasing visibility for under- or mis-represented groups. It draws on a tradition that flows through a range of disciplines and fields — like health communication, behavioral science, psychology — and creative people, like playwright Bertolt Brecht, who viewed theater — his particular medium — as a revolutionary venue for participation and discovery powerful enough to reconstitute a body politic. The power present day media systems put at our disposal would have been unimaginable to Brecht. If, as recent media stories suggest, we are already in another period of significant cultural reconstitution, then we had better start figuring out how we intend to use that power.

Here are some questions we’ll be asking, as we continue this work and move beyond small podcast pilots to a series on one of the streaming services perhaps? :)

Asch is the founder of Red Hook Media Lab and executive producer for “Anomaly.” He has spent the last decade working at the intersection of democracy, design, and technology at organizations like the Council on Foreign Relations and UNICEF.

Brian is the Executive Director of Harmony Labs and executive producer for “The Audience.” Before Harmony Labs, he served as managing director at Institute of Play. He also served on the core founding teams for Quest to Learn, a New York City public school that leverages game design to make school engaging and culturally relevant for young people; and GlassLab Games, a Silicon Valley development shop transforming digital games, like SimCity, into classroom learning environments with real-time formative assessments built in.