Four Principles For Building Power in Media

2025-11-12

If you’re drawn to the idea of solidarity, you probably already believe in the power of community. You see the value in being “in it together,” whether that’s in organizing spaces, talking circles, or movements for justice.

At Harmony Labs, we’ve been working alongside organizers and narrative strategists to support their work on poverty and self-governance in the U.S., as participants in the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Mindsets Consortium on health and racial equity, and most recently as advisors to the Asian American Futures (AAF) in their work on Asian American cross-racial solidarity.

That collaboration made us curious about what solidarity actually is, and how it’s created and sustained.

We surveyed 600 Americans, oversampled by race, to explore cross-racial solidarity. We asked about four things:

Using causal modeling, we tracked how these elements influence each other across group pairings—Black respondents about Latino and Asian Americans, Latino respondents about Black and Asian Americans, White respondents about Black and Latino Americans, and so on.

When people already feel connected, they readily work together on shared goals (what we call instrumental solidarity) and show up for each other’s causes (altruistic solidarity). Friendships fuel both. Other researchers have also found that cross-group friendships predict action in solidarity, especially when everyone in the relationship recognizes that inequities are unfair.

But many Americans aren’t already close across racial lines. So how do we start?

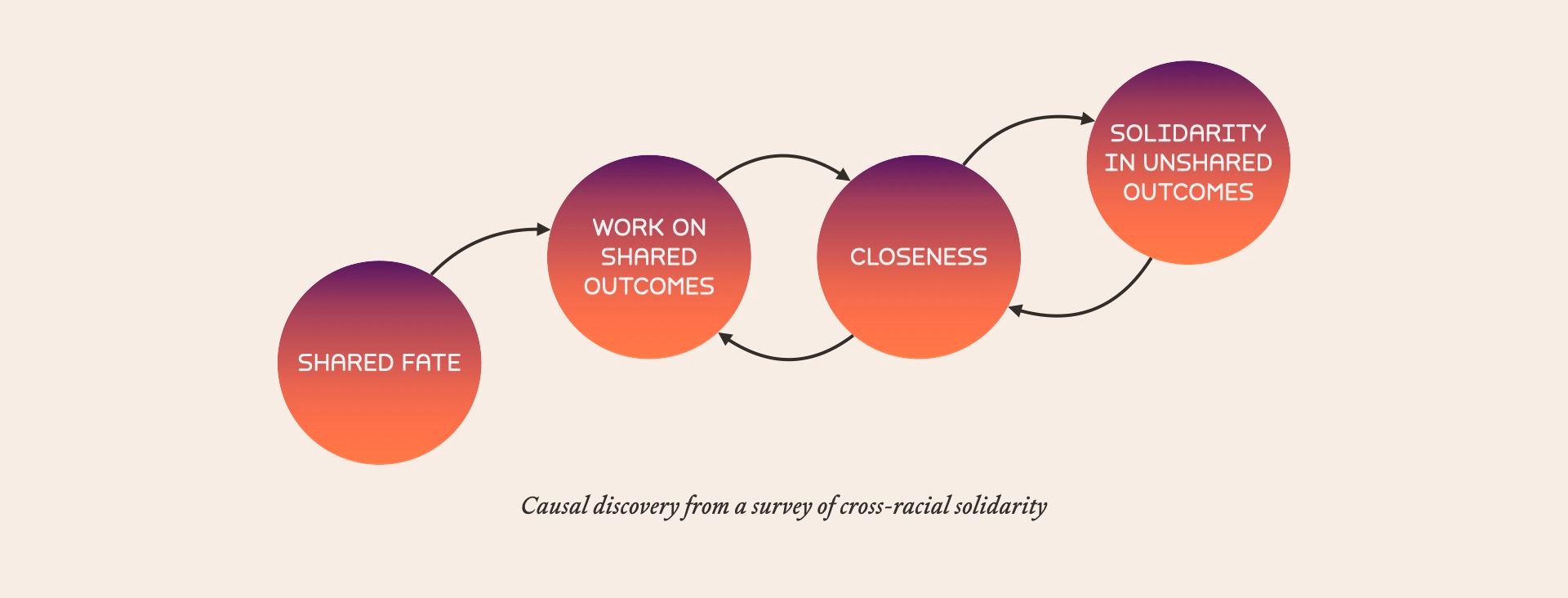

The only clear causal pathway we found was shared fate leading to collaborative work. When people recognize that their communities face the same barriers to economic success, healthcare, or justice, they become more willing to work together to overcome them.

Solidarity begins when people see that their fates are linked. The data confirm what decades of social psychology have shown: intergroup cooperation grows both from shared goals and interpersonal contact. But most importantly, shared work sets the process in motion.

Once people begin working together on shared goals, that collaboration builds closeness. The work itself strengthens bonds, and those bonds, in turn, make people more likely to take further action in solidarity.

If the key question for our partners is how to invite others into the tent, then this research suggests that the answer lies through the work, rather than just the community.

For many organizers, solidarity already feels foundational to coalition-building. It’s how they start. But for people outside organizing spaces, solidarity isn’t the entry point; it’s the outcome of doing meaningful work together.

Narratives that activate solidarity need to start with shared fate and shared outcomes, not just shared values. They work best when they invite people into purposeful collaboration, rather than asking them to feel connected before they’ve had a chance to act together.

At the same time, this doesn’t mean abandoning “community.” The implication for coalition-building—especially where closeness doesn’t already exist—is that solidarity can grow through the work, not before it. This means designing work structures where everyone who participates has a clear role in creating outcomes everyone wants. We used causal modeling to test this idea, but we didn’t conceive it. Durkheim observed in 1893 that structured roles bring about social cohesion. More than 125 years later, that insight still holds true across races and issues.

The pathway to Durkheim’s organic solidarity across groups and issues is:

If you’d like to learn more about this research or explore what building solidarity could look like in your community or organization, we’d love to hear from you.

We surveyed 600 US respondents (200 White, 200 Black, 200 Latino). White respondents also answered about Black and Latino people, Latino respondents answered about Black people, and Black respondents answered about Latino people. Everyone answered questions about Asian Americans. No one was asked about solidarity with White people.

We measured four constructs:

Shared fate (across three domains—healthcare, economics, and policing):

Instrumental solidarity (on economics):

Pure solidarity: “I am willing to actively support issues that primarily affect [Asian American/Black/Latino/Hispanic] communities, even when they don’t directly impact [respondent’s group].” (5-point scale from “Strongly disagree” to “Strongly agree”)

Modeling: We used a method called causal structure inference to determine which events in the story of solidarity caused each other directly and which were bidirectional. For instance, perceived shared fate directly caused work in solidarity on shared goals. Closeness both caused work in solidarity and was reinforced by that same work in a bidirectional relationship.

Different races: Our goal here was to use examples of cross-racial collective action to create beliefs about how people come to the work of solidarity across group identities and issues. To do that, we measured self-reported shared fate, closeness, and solidarity between a sample of the possible pairs of groups:

To create an understanding of whether the findings held across groups, we analyzed each of these pairs separately and compared. The three findings from all this post were all true in all groups. They might be different in other group contexts or for issues outside of healthcare, policing, and economics, but the sample of issues and groups here was quite consistent.