Audiences for Climate Communications

2024-09-11

For a while now, the practice of working with narrative to produce social change has been fashionable. As a result, everyone seems to have a definition of narrative. (Our favorite is this one from FrameWorks Institute: “Narratives are patterns of meaning that cut across and tie together stories. They both emerge from . . . and provide templates for specific stories.”) But there is less specificity about how to actually identify a narrative; how to understand its intersection with or dominance across audiences; how to know if it’s growing, spreading, or otherwise evolving; and how to evaluate at scale the performance of narrative interventions. In other words, the actual practice of working with narrative is significantly less well described than the high-level ideas and theories which tend to fascinate. So, in the spirit of helping to fill that gap, we thought we would make visible how we work, at the most fundamental level of extracting patterns of meaning from media, and share some of the things we’ve learned about analyzing media to support narrative strategy.

First off, whatever analytic approaches we use derive from the questions we’re trying to answer and the needs of our partners. For partners who want to engage in long-term narrative tracking, for instance, we will use narrative identification methods that afford efficient model training and tuning. The work we detail in this post came from a partner who wanted to investigate ultranationalism narratives, in order to understand how they were coming to life online. Our partner wanted to know the extent to which these narratives attracted young men under the age of twenty-five, and they needed results fast on a tight budget. So we chose an analytic approach that could quickly yield an actionable impression of the key thematic patterns underlying ultranationalism narratives for young men on YouTube. But regardless of whether we’re doing quick impressionistic analysis, or building narrative models, there is coherency in how our methods scale. Which is to say, for now, we view the pattern recognition required for narrative identification as human work, supported by machines, and we conceptualize and approach that work more or less in the same way, whether it’s performed by a lone analyst or a couple dozen annotators, researchers, data scientists, and engineers.

We start by computationally building samples of media content for analysis. Typical constraints for media content samples are: platform, media format, audience, time period, and prioritization metrics like average daily reach, audience distinctiveness, or topical relevance. In this case, constraints were: YouTube, a platform which serves all sorts of audiences with all kinds of content, and therefore affords abundant opportunities for narrative intervention; videos and shorts; men under the age of twenty-five; thirty-two months between 2021 and 2023; a prioritization constraint derived from clusters of channels built by audience behavior; and relevance to ultranationalism. Of course, samples are also constrained by the volume of media content appropriate to our analytic approach and desired outcomes. In this case, here is one media sample that arrived in front of a single analyst in the form of a spreadsheet:

As analysts, we strive to approach whatever we’re analyzing with all the objectivity we can muster. After all, our project is not to understand the meaning we might make from the videos we analyze, but rather to discover all the possible features that might have attracted young men to engage. By objectivity we do not mean a cold, distant, impersonal attitude, or a view from nowhere. We mean a balanced, sustained combination of focused attention on the media content, moment-to-moment awareness of our own physical and mental states, and equanimity. We mean setting aside, as much as possible, all our judgements, theoretical frameworks, ideological commitments, emotional reactions, and meaning making habits, or at least bringing into awareness how all these might be interacting with our experience. We are looking for as bare, direct, and complete an encounter with the media content as possible, an out-of-fashion observational practice we learned by studying art history and philology.

Habits of mind that support this kind of balanced attitude include curiosity and wonder. Of all the trillions of pieces of media content in the world, someone chose to pay attention to this one, and because of that, I too will pay attention to it! We do our best work when we adopt this kind of attitude. Have you ever walked through the woods and come across a wild animal and locked eyes for a moment? We think of the media we analyze in this way: as something wild and true from another world, which we are fortunate to briefly encounter.

It is not always easy to maintain this attitude. We often confront content that is violent, sexual, racist, misogynist, homophobic, anti-semitic, and other flavors of hateful, shocking, disturbing, and/or transgressive. Our job is not to flag such content and move on, like many content moderators, but to engage with it fully and analyze it deeply. For this project, that meant more than 30 combined hours of video watching. There are strategies and resources in circulation for doing this kind of work more safely (like this one, this one, or this one) to minimize vicarious trauma for people documenting and verifying human rights abuses, for example. We use many of these strategies, according to the safety plans we have in place. Mostly though we only work with difficult content in the morning, when we are well rested, not hungry or thirsty, and at our most alert. We use small screens, multiple minimized windows, take notes with pencil on paper, and break often . . . anything to keep awareness inside our bodies and to create the kind of Verfremdungseffekten (“Distancing Effects”) playwrights like Bertolt Brecht used to minimize emotional identification and maximize criticality in theatrical audiences.

Our most effective tool for working with difficult content, however, is probably our analytic method. We imagine content as having many attributes or features, which different viewers will experience differently, and which, in the case of video, also change over time. Here is an example of the kind of table we use for moment-to-moment observation and analysis of media content. It is filled out for one of the videos in the sample we showed above: a two-minute edit of anime clips depicting a budding boy-girl relationship, titled “Sumi-chan is the cute introverted waifu we all want.”

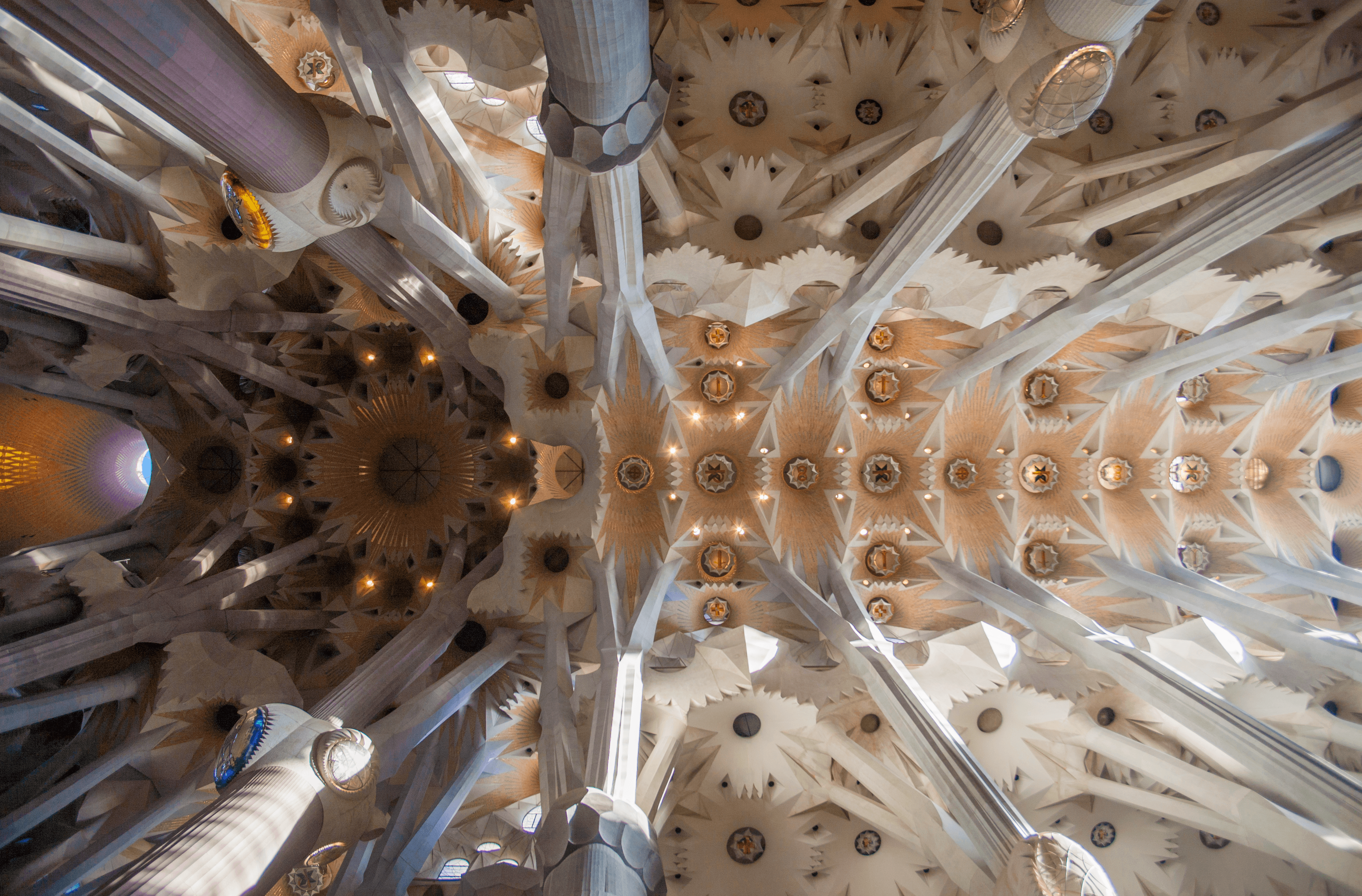

Making observations in this way helps us maintain the kind of objectivity discussed above, in which all the elements of the media content stand in equal relationship to one another, shivering like electrons in a state of potentiality and possibility, waiting to encounter the magnetic, meaning-making gaze of a viewer. Perhaps it is more evocative to visualize the state of equilibrium we’re striving for in this way:

Making observations in this way helps us maintain the kind of objectivity discussed above, in which all the elements of the media content stand in equal relationship to one another, shivering like electrons in a state of potentiality and possibility, waiting to encounter the magnetic, meaning-making gaze of a viewer. Perhaps it is more evocative to visualize the state of equilibrium we’re striving for in this way:

Mainly what we are seeking to resist in our observations and analysis is the tendency to allow one or several attributes, features, or moments in time to stand in for or come to represent the whole. Letting one part stand in for the whole is probably human nature, a useful device for reducing complexity, making meaning, building story, emphasizing relationship, or avoiding harm, which even has a literary name: synecdoche. But synecdoche is the enemy of thorough analysis. We feel ourselves pulled toward synecdoche especially in moments that trigger painful or traumatic associations. In this video, there were three such moments, indicated on the spreadsheet above with lightning bolts. These moments threaten to blind us to whatever else might be happening in the content, throwing out of balance the attentional equilibrium we strive to hold. To be triggered is to be momentarily blinded, our awareness consumed by one aspect of experience. Trigger warnings can be useful tools for approaching such moments mindfully and moving through them in a way that maintains integrity of observation. Or it may be that we need to step away and take a break, or totally discontinue our analysis.

Mainly what we are seeking to resist in our observations and analysis is the tendency to allow one or several attributes, features, or moments in time to stand in for or come to represent the whole. Letting one part stand in for the whole is probably human nature, a useful device for reducing complexity, making meaning, building story, emphasizing relationship, or avoiding harm, which even has a literary name: synecdoche. But synecdoche is the enemy of thorough analysis. We feel ourselves pulled toward synecdoche especially in moments that trigger painful or traumatic associations. In this video, there were three such moments, indicated on the spreadsheet above with lightning bolts. These moments threaten to blind us to whatever else might be happening in the content, throwing out of balance the attentional equilibrium we strive to hold. To be triggered is to be momentarily blinded, our awareness consumed by one aspect of experience. Trigger warnings can be useful tools for approaching such moments mindfully and moving through them in a way that maintains integrity of observation. Or it may be that we need to step away and take a break, or totally discontinue our analysis.

We perform this kind of observational analysis on all the pieces of media in our sample, one by one. Then we look for similar or common features, in this case, patterns which help describe how young men encounter the ultranationalism narrative.

In this thirty-minute reaction video, titled “EDP445 Situation,” YouTuber penguinz0 scrutinizes the online trail left by Predator Poachers, “a group of independent journalists and private citizens who conduct intervention-style sting operations to catch child predators,” in their effort to entrap EDP455 by posing as a thirteen year-old girl online. As penguinz0 rehearses and comments on text chats and videos in graphic detail, two moments stand out as points of possible relationship to the Sumi-chan video above. The first is when penguinz0 portrays EDP455 as inexperienced and un-sauve. The second is when Predator Poachers portray the girl persona as incompetent and in need of “teaching.”

This pattern of a boy, initially shy or inexperienced, who gains self-efficacy, superiority, power, and/or prestige by being in relationship to an incompetent girl was the most frequently occurring commonality in the analyzed content. It represents a strong association network inside of the ultranationalism narrative, as experienced by young men. And it suggests that young men engage primarily with the first beat of the ultranationalism narrative, the idea that society has become decadent, impure, degraded, a degradation that tends to center the “natural order” of traditional male-female gender norms.

This is how we identify patterns in the media content audiences engage with that form a basis for narrative identification, or characterization of how particular narratives show up for different audiences. We also look for features unique to individual videos that might tell us something important, emergent, or strategic about an audience or a narrative. Take, for instance, this talk-back video by YouTuber Destiny, titled “Ben Shapiro Tries To Hide What He Really Thinks.” Destiny offers a detailed point-by-point rebuttal of Shapiro’s remarks that models fact checking and coherent, well reasoned, evidence-based argumentation. We flagged this in our analysis as a possible model for resilience building that young men were already engaging with, which could be interesting for our partner to explore and experiment with.

This is how we identify patterns in the media content audiences engage with that form a basis for narrative identification, or characterization of how particular narratives show up for different audiences. We also look for features unique to individual videos that might tell us something important, emergent, or strategic about an audience or a narrative. Take, for instance, this talk-back video by YouTuber Destiny, titled “Ben Shapiro Tries To Hide What He Really Thinks.” Destiny offers a detailed point-by-point rebuttal of Shapiro’s remarks that models fact checking and coherent, well reasoned, evidence-based argumentation. We flagged this in our analysis as a possible model for resilience building that young men were already engaging with, which could be interesting for our partner to explore and experiment with.

How we analyze content has evolved over decades of trial and error, in tandem with the evolution of computational tools that support this work. At university in Tübingen, Sem remembers standing to watch the only available television, on a high dresser in a friend’s room, neck bent uncomfortably upward . . . an early lesson in maintaining alert criticality. And Brian remembers “reading” literary texts backward to better identify textual features that the emotional flow of a story’s forward movement might otherwise subsume.

There is something paradoxical in how much energy and active intention is required to maintain the open, yet focused awareness that supports effective observation and analysis. And there is something incredibly energizing and eye-opening about finally achieving it, finding yourself on the opposite shore from all the likes, dislikes, and other judgements that make up the everyday exercise of personality . . . resting for a moment in the bright spaciousness of undifferentiated experience. We know this from our analytical work with media, and also from the meditation practices we have cultivated over the years. These two types of work share important borders. Both contribute to our ability to be more fully with all that exists, the beautiful and the terrible, wherever we find it, in ourselves, in others, in the stories we tell in the media, and IRL. The French philosopher-mystic Simone Weile, in her First and Last Notebooks, observed, “Attention is the rarest and purest form of generosity.” We heartily agree.

Check out the full report on ultranationalism or get in touch to start a conversation.

Title image by Doc Searls.