Four Principles For Building Power in Media

2025-07-30

This is Part III of our ongoing survey dispatch capturing audiences’ evolving deep stories on equality. You can read Part I, Part II, and Part IV here.

We are in an era marked by intense debates over sweeping policy changes to healthcare and other benefits that are poised to reshape the social safety net. NPR calls it “a dramatic realignment of the federal government’s role in American life.” Understanding how people judge deservingness and resource distribution now is vital for shaping narratives around social programs designed to bring about fairness and equity, because they affect millions of lives daily.

One way progress toward equality can be measured is by moving people to appreciate equity, or the process of making it easier for some groups to flourish in order to balance disparities:

Equity will drive healing. Historic inequities won’t heal themselves. To achieve equality now, we will need to make it easier for some groups to flourish while we achieve balance and eliminate disparities.

Since both equality and equity are necessary parts of the narrative goal of systemic equality, we measured progress toward these two very different ideas through our Deep Story Survey System. In this dispatch, we study perceptions about group equality, fairness, deservingness, and resource distribution to understand how different audiences think about equity-driven resource distribution.

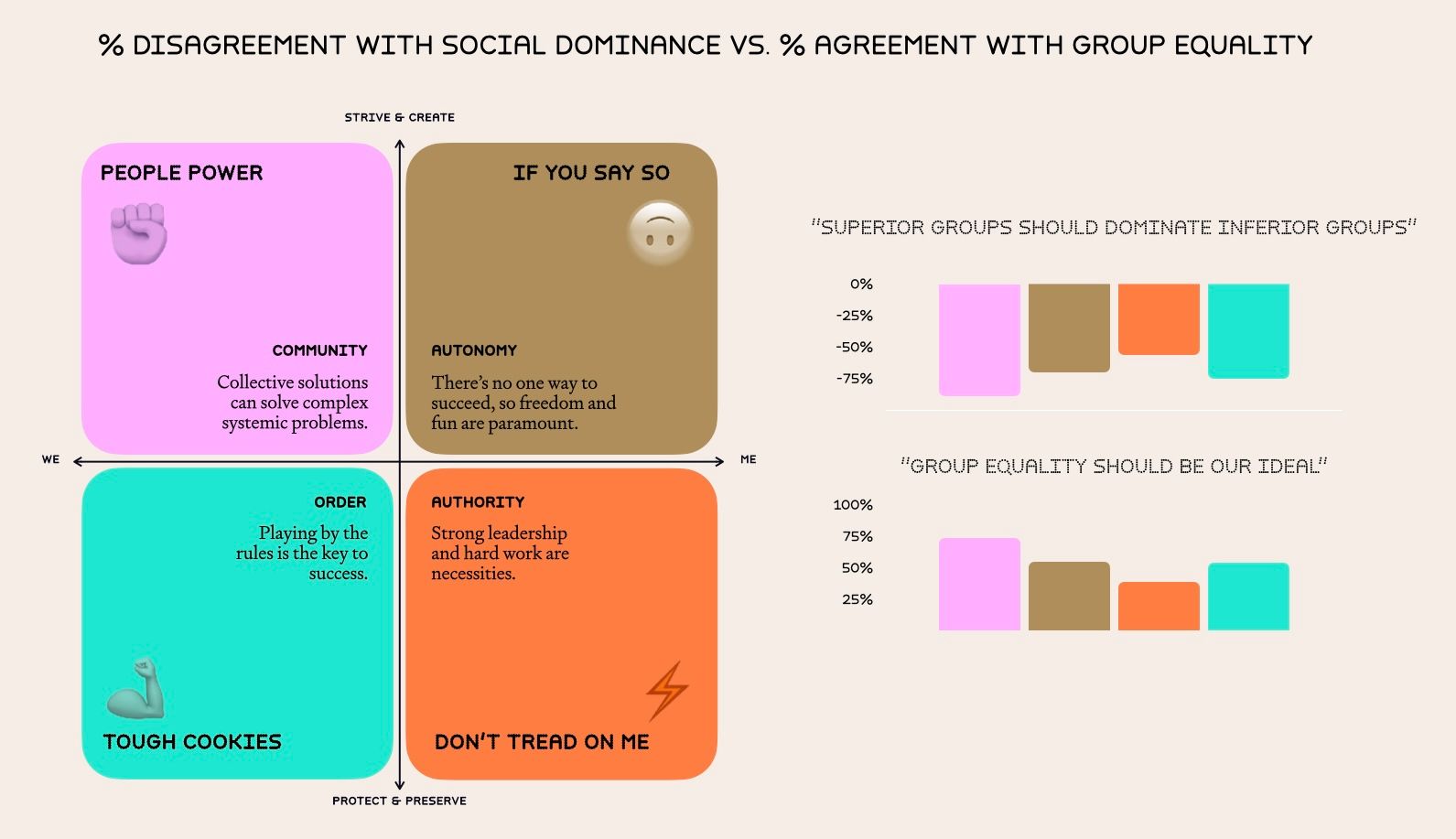

Social dominance is unpopular across all four values-distinct audiences (you can learn more about those audiences here), and the idea that “superior groups should dominate inferior groups” is widely rejected. People Power leads with 89% disagreement, followed by If You Say So and Tough Cookies at ~70% disagreement. Even among authority-oriented Don’t Tread On Me, a majority (56%) disagrees, showing that explicit social dominance is not favored across the values spectrum.

Even though audiences aren’t enthusiastic about maintaining social hierarchies, they’re not completely bought into pushing for group equality either, which suggests that people hold different positions about how society should be organized. Power Power, as a community-oriented audience that embraces collective responsibility, strongly supports group equality as an ideal (74%), but Don’t Tread On Me shows much less support (39%), while If You Say So and Tough Cookies fall in the middle, with just over half agreeing.

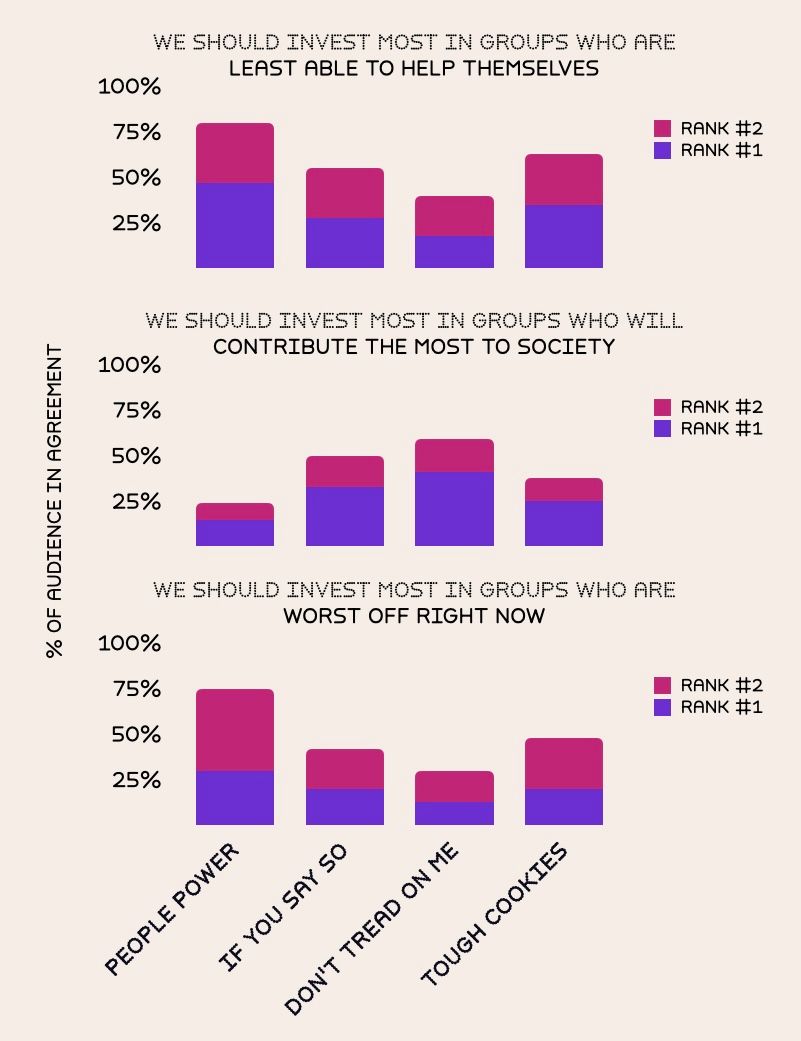

Deservingness judgments: harmful or universal? Just as people hold divergent visions of how society should be organized, they also differ in their perceptions about which groups are deserving of help. We wanted to understand how audience values determine beliefs about who society should invest in. While all five CARIN deservingness principles were considered in the survey, three emerged most prominently in participants’ responses: control, reciprocity, and need. Attitude and identity appeared less influential in shaping views on who most deserves support.

Collectivist audiences like People Power and Tough Cookies tend to see a moral obligation to help the most vulnerable or blameless, though some still view their support as conditional. Individualist audiences like Don’t Tread On Me and If You Say So are more likely to see resource allocation as a strategic investment, where help is earned rather than simply granted.

Regardless of the differences in these judgments, the data reveals that all audiences use some form of deservingness to make judgments about resource distribution. While some see “deservingness” as a harmful mindset, the findings show that judgments about who deserves help are not only common, they are universal. Understanding how each audience thinks about deservingness offers clues for framing stories and policies that resonate with their values.

While some see “deservingness” as a harmful mindset, the findings show that judgments about who deserves help are not only common, they are universal.

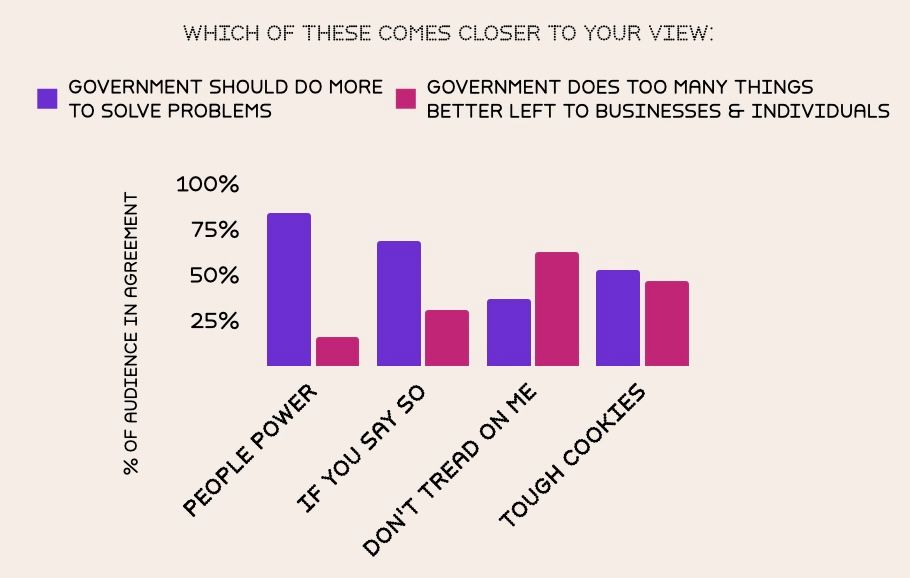

Beyond differences in beliefs about which groups deserve resources, there are also divergent views on who should take responsibility for equitable resource distribution. People Power overwhelmingly supports an expanded government role, with 84% agreeing that “the government should do more to solve problems,” while Don’t Tread On Me prefers limited government, with 63% believing that “government does too many things better left to businesses and individuals.”

Both positions show stable, principled beliefs about how societies function best and who should be held accountable. The opportunity lies in telling stories that don’t frame the choice as either government or the private sector, but instead highlight that all actors—government, businesses, and individuals—can play meaningful roles in addressing disparities. This inclusive framing may resonate especially with audiences like If You Say So and Tough Cookies, who are less politically engaged and show genuine ambivalence about the government’s role in resource distribution.

Audiences’ definitions of fairness are deeply shaped by their beliefs about who deserves help. Think of fairness and deservingness as two sides of the same coin: if the people you believe deserve investment are being supported and are succeeding, then you perceive that society as fair.

Not surprisingly, for individualist audiences, a fair world is one where resources are distributed based on individual effort and contribution. 69% of Don’t Tread On Me and 65% If You Say So prioritize merit-based fairness the most, ranking a society where “hard-working people earn more than others” as the first or second best type of fair society. This belief in earned rewards and incentive structures is further validated by authority-oriented Don’t Tread On Me, 67% of whom agree that “people who receive government assistance should be required to give back to society in some way (such as through community service, job training, or working).”

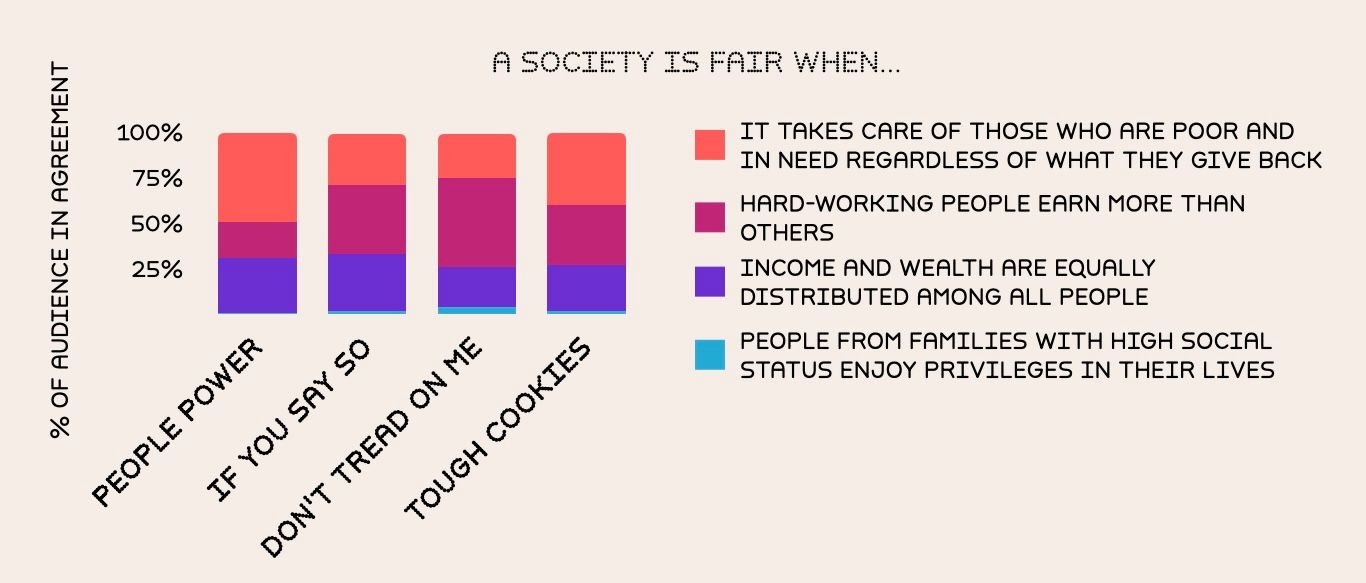

On the other hand, 83% of People Power and 79% of Tough Cookies, as audiences who value universalism, are most supportive of the view that “a society is fair when it takes care of those who are poor and in need regardless of what they give back to society.” This belief about collective responsibility is consistent with People Power’s high agreement (72%) with equity-based fairness, or “ensuring that all groups have similar levels of success, even if it requires giving some groups more assistance.”

Notably, over 50% or more of all audiences rank entitlement, or the idea that high social status should confer privileges, as the least fair model of society.

Only when people see themselves (or someone they can relate to) transformed for the better as a result of a system that eliminates disparities and enables flourishing, will they believe that equity can drive systemic healing.

The first step is to respect the diversity of values that shape people’s core beliefs about what is fair, who is deserving of help, and who is responsible for eliminating disparities, rather than requiring audiences to abandon them in the pursuit of an equal future. The challenge is in creating stories that acknowledge these values, yet feature relatable characters who support equity-enhancing solutions.

Individualist audiences may need to see how systemic barriers can prevent even the most hard-working from succeeding and how removing systemic barriers benefits everyone, rather than creating winners and losers. Collectivist audiences who prioritize blamelessness may need to understand the systemic reasons why people struggle, and why empowering everyone to flourish is a collective good.

In the next survey dispatch, we’ll explore narrative opportunities to tell new stories about systems and individuals that could reflect and affirm each audience’ superpowers. Read Part I, Part II, Part IV, and subscribe to our newsletter for updates about our latest research.