Four Principles For Building Power in Media

2023-02-27

The work of advocacy is commonly conceived as an effort to influence or win people over with a different point of view —often our own point of view—to change how people conceptualize themselves, others, or the world we share, in support of some important goal. The pioneers and perfecters of advocacy as mass influence were the missionary church, military intelligence, and consumer capitalism. These institutions still linger in the language of advocacy. We speak of conversions, engagement, strategy, tactics, targets, impact, our base and opposition, of “winning hearts and minds.” Implicit in this language is a view of human beings as instruments of larger powers and purposes, tools that must be moved, tuned, or activated by forces external to their will. And this implicit view is often at odds with the explicit goals of advocacy, especially when those goals are deep, complex, and long term, like changing how we relate to planet and place, for instance, in response to the climate crisis. Instrumentalize people often enough, and their capacity for independent discernment or autonomous moral action will certainly diminish. Is there another way?

We think so.

Some work we recently completed with support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation in collaboration with Story Strategy Group points to a different way to think about advocacy. The work was about how people in the U.S. encounter health and equity in the media; the health and health equity narratives that arise from audience encounters with media; and how media content might help shape and shift those narratives. There were a couple big surprises.

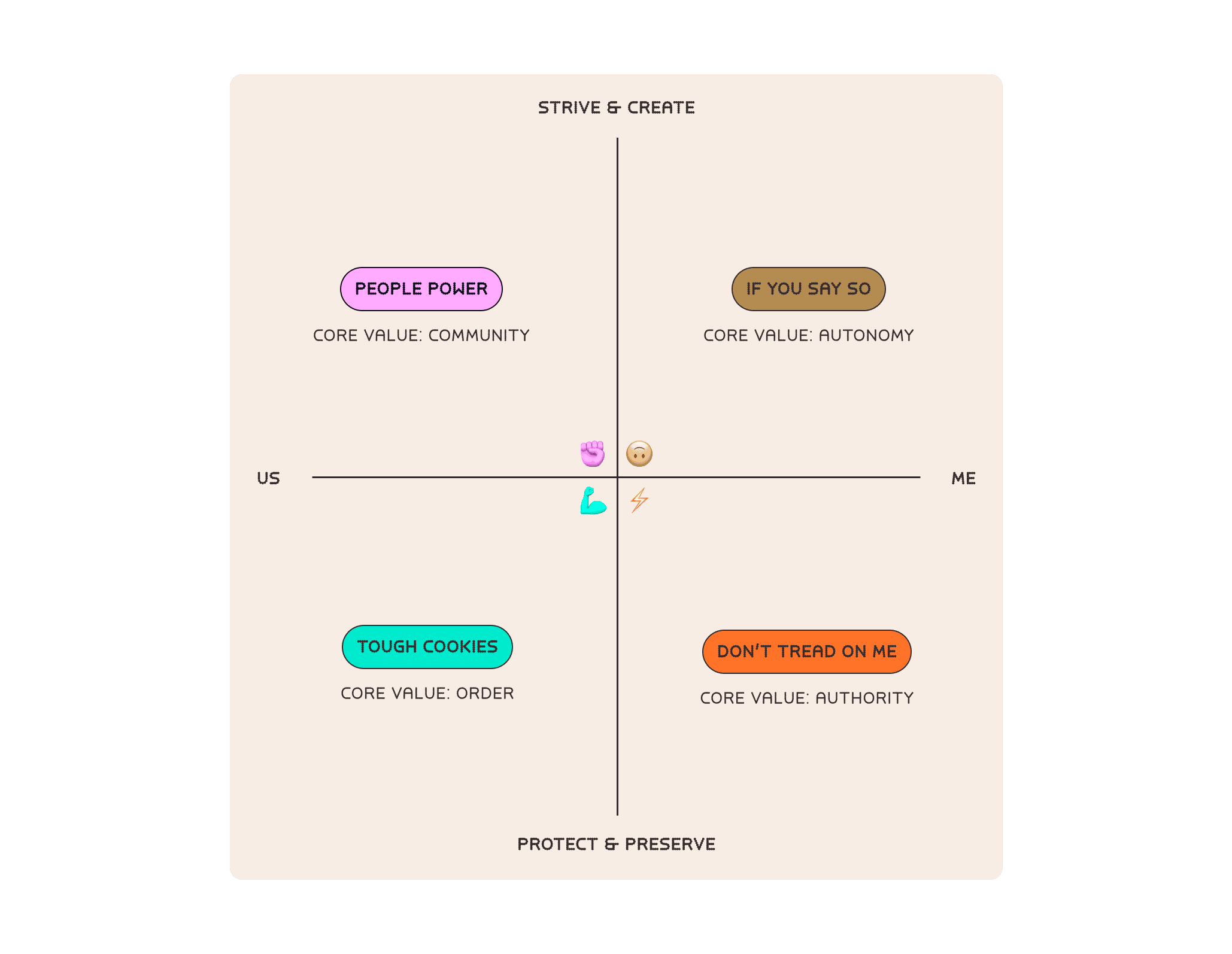

But before we dig in, we need first to ask what audiences are, and what role they play in advocacy work. Google tells us that audiences are “the assembled spectators or listeners at a public event.” Once upon a time, audiences formed when people assembled in person, in the same time and place. Nowadays, we tend to assemble in, with, and through media, virtually and asynchronously, often and everywhere. This can make defining what is coherent and distinctive about an audience challenging. In our work, we’ve found that values are excellent predictors for how people assemble into media audiences. This makes intuitive sense. Values are the things we ascribe particular importance to. They’re like goals or happy endings. So, of course, we seek out and engage with media that bring to life our happy endings, that reflect and reify what we value.

For this reason, in our work, we use values (specifically clusters of values derived from Shalom Schwartz's theory of basic human values) to segment people into audiences, and we use audiences to explore and describe how people engage with media. At the highest level, our segmentation comprises four audiences, placed on the x-y axes to the right. Audiences in the top two quadrants hold values related to exploring and creating, while audiences in the bottom two quadrants value protecting and preserving what they have. Audiences to the left tend to orient more toward the collective, whereas audiences to the right skew more individualistic. Like all segmentations, our audience segmentation gives advocates a way to reason about a reality where every human being is unique, and to strategize about how to speak with broad groups of people who share values, attitudes, or behaviors. Unlike segmentations based on demography or political support, however, this audience segmentation has the added benefit of corresponding to how people actually exist inside of today’s media culture. So, when the time comes to make a campaign or to buy media, it can tell us about the content, voices, and platforms that are already resonating with audiences.

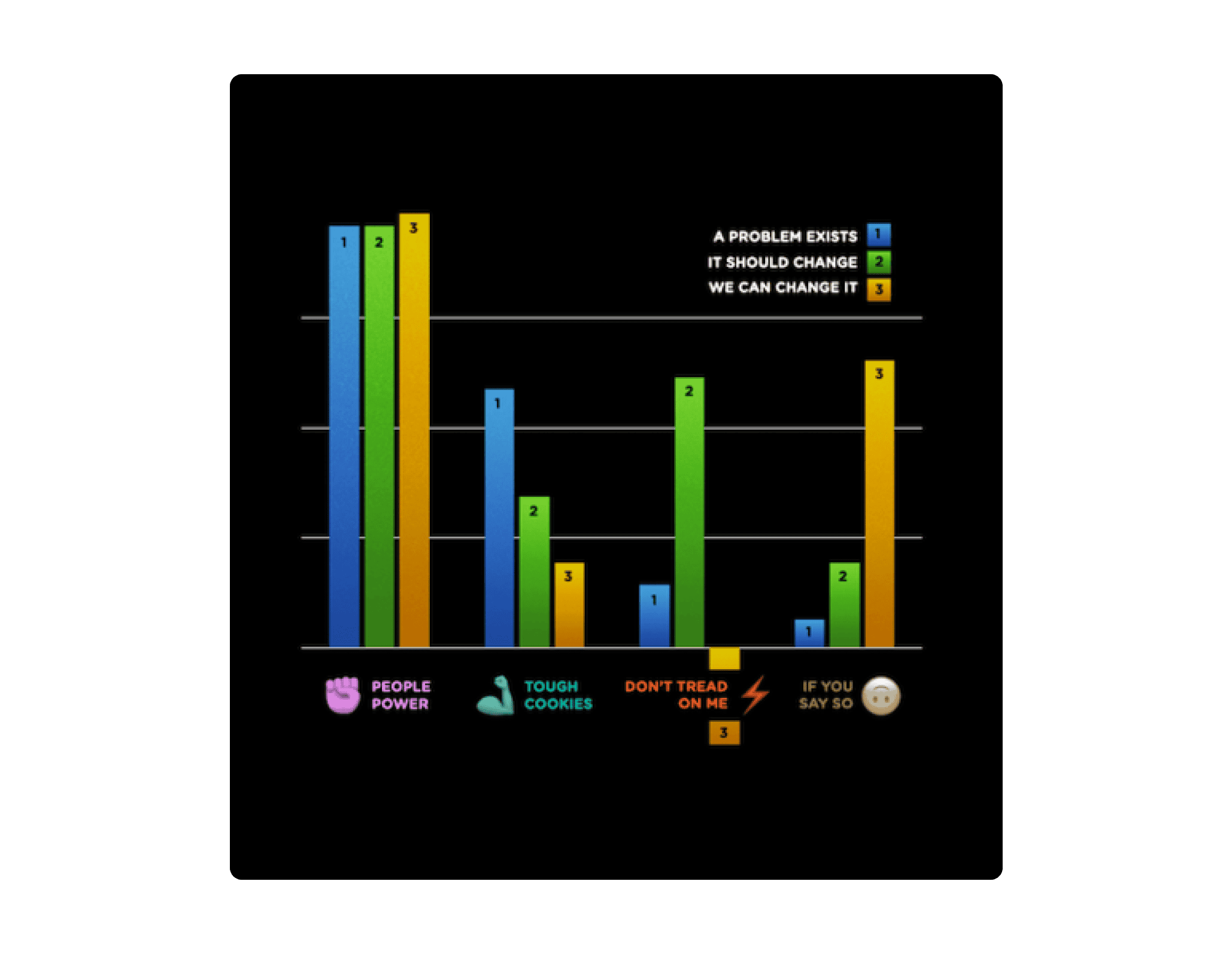

Now that you have the basics of how we think about audiences, let’s return to the two big audience-related surprises in our recent health equity project. The first surprise was that the social media content we created actually transported all U.S. audiences to endorse a narrative on health equity that:

The particular surprise here was that our content transported even the audience we call Don’t Tread on Me. This is the audience whose values center authority, and which tends, on average, not to acknowledge that white people are treated better than people of other races in healthcare settings. So it caught our attention when Don’t Tread on Me not only acknowledged the harms of medical racism, but also endorsed change, even despite perceived personal trade-offs. Stories featuring choice and control served as narrative entry points for Don’t Tread on Me. Each of our other three audiences had different entry points, which you can learn more about in our full report on this work, which includes the stories and social media content we used for testing.

But it wasn’t only the entry points to the narrative that differed by audience. Different audiences also gravitated more strongly toward different parts of the narrative. We could see this, because for testing we broke the narrative down into the three parts described above. These three parts roughly correspond to the beginning, middle, and ending of the positive narrative on health equity this project seeks to grow. Breaking the narrative down in this way allows us to move beyond testing for simple message agreement, to start observing more about how people respond to stories in their day-to-day media interactions on different platforms and devices. This differentiation in the way audiences gravitated toward narrative beginnings, middles, and endings was the other big surprise from the project. And this is the finding we think suggests a different way to think about mass advocacy.

So what exactly did we find? When we averaged the effects observed in audiences from treating them with social media content, we found these effects generally corresponded to the values and health-related narratives that define each audience. Which is to say, for example, the Don’t Tread on Me audience gravitated most strongly to the second part of the narrative, the part that demands change. This accords with Don’t Tread on Me’s value on authority and strong leadership, their orientation toward action, especially in the face of adversity and against perceived opposition or enemies. The audience we call Tough Cookies, by contrast, which values social order, safety and security, was most attuned to the threat of inequity in healthcare, and so gravitated most strongly to the first, problem-focused part of the narrative. Whereas the imaginative, autonomy-focused audience If You Say So gravitated most strongly to the third part of the narrative, which imagined an equitable future.

Perceiving a problem, demanding change, and imagining pathways to effect change are essential components in any narrative that supports a new future. And inside of this narrative structure, there is a place and potential contribution for each of our four audiences, one which does not require a change in their basic values, but rather brings those values into the service of a new future as features, not bugs, as strengths to power the different parts of the process of change. This is good news, because every society is bound to contain a diversity of values. Not everyone will live all the time in the values space of Community, Universalism, and Benevolence, which define the audience we call People Power. And advertising, at least at the scale of most advocacy work, is probably not powerful enough to occasion durable changes in what people value.

When commercial game designers design a game, they often think about and test how best to integrate the behaviors of all potential players, even the lurkers and loners who shun goal-oriented play. This is not only more inclusive, it’s also good business, insofar as it creates a game that accommodates a broader base of players. In the same way, we imagine a model for mass advocacy that looks less like advertising and more like organizing. Less like dividing the world into us versus them and engineering the “us” to consent to a limited set of viewpoints, and more like designing narrative spaces that reflect how people with different experiences and values collectively see themselves, others, and the world we share. In this way, more people will feel more at home in the narratives that are likely to afford a new future, and also have a role to play in propagating those narratives.

What would this look like in practice? This we need to continue to explore and discover, together with more partners working not just on equity in healthcare, an issue most people in the U.S. can agree requires attention. But we already know some of the questions we need to ask to evolve our practice, to move us away from the notion that there is always some percentage of the population we need to instrumentalize or “fix,” in order to realize some brave new world. For instance:

Asking these questions and evolving our practice may just be the difference between actually making progress on the issues we care about in a way that brings everyone along, or continuing as a people to fragment and polarize as our planet burns. If you’d like to join us in our exploration of what an audience-centered model for mass advocacy could look like, and how it could start to enact the positive, pluralistic, inclusive society much of the work we support strives to bring into being, please be in touch.